Breamore, Hampshire

Review

The Anglo-Saxon invaders establish themselves in Britain

In the late third century, the Picts and Hibernian Scots in the north and west were joined in increasingly serious acts of piracy and raids upon the coasts of Britannia by Germanic people of tribes known as Angles, Jutes and Saxons from the Baltic and the Frisian coast area of the North Sea. Romano-British forts were erected along the ‘Saxon Shore’ and, for a time, they successfully repelled the brigands and pirates. However, as Roman rule in Britannia collapsed in the early fifth century, the Germanic raids from Europe flared up again. Although there is no evidence that the raiding parties ever joined forces to become a single military force, it appears the British defenders were unable to put up much resistance.

[swpm_protected custom_msg='If you wish to read or listen to the complete account of this section and gain permanent access to all the other parts of Annals Britannica, please Login now or Join via Credit/Debit card on PayPal for only £5.']

Finding only feeble opposition, the raiders became more emboldened. It is sometimes claimed that much of their homeland was swampy and subject to flooding and they were attracted by the green and fertile fields of Britannia. It is also likely that the migrations of various other peoples, including marauding Goths and Vandals, added to the unease of those Germanic tribes living along the North Sea shores and caused them to seek safer homes across the sea.

They began to establish sporadic settlements in Britannia. It is believed that sometimes the local British leaders hired armed bands from those areas as mercenaries and invited them to settle, and that the mercenaries eventually rose and took over control from their British hosts. Large scale migration of their kinsmen then followed. They originally settled around the coastal areas and river valleys of eastern and southern Britannia, perhaps killing, driving out or enslaving most of the Romano-British natives. In the early sixth century the mythical British King Arthur is credited with a military victory against the newcomers which for some time halted their expansion into the heartlands of Britannia. However, by the end of the century the Germanic settlement was mostly complete and the country, comprised of a number of petty kingdoms, began to be known as Angleland or England.

The newcomers probably spoke a number of dialects of North German origin which eventually coalesced into the Old English language. It is thought that most of the original British inhabitants who escaped death or slavery had retreated into the fastnesses of Wales, Cornwall, Cumbria and the Strathclyde region of Caledonia where they continued to speak their native Celtic/Gaelic languages. They also continued to hold some Christian belief, whereas the newcomers were pagans.

The old Roman towns and forts fell into disrepair and the vast bulk of the Anglo-Saxon newcomers established themselves as country dwellers and farmers. We tend to think of them as individual farmers but in some places it is likely that they adopted a communal form of arable agriculture, a forerunner of the medieval manorial system.

By the end of the sixth century, seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were well-established in most of the old Britannia. The Angles settled what became known as the kingdom of Northumbria, consisting of most of the land north of the River Trent up to and including Lothian in Caledonia. Angles also settled East Anglia which bears their name to this day. Saxons inhabited the kingdoms of Wessex, Sussex and Essex. It is claimed that Kent was mainly a Jute kingdom, as was the Isle of Wight. Mercia, which eventually covered all the Midlands, possibly consisted of a mixed Anglian and Saxon population.

Internecine feuds and dynastic rivalries constantly led to outbreaks of warfare both within and between the kingdoms. During the seventh century, the two kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria vied for superiority under the leadership of powerful kings. King Penda, who ruled Mercia for about 30 years until his death in 655, eventually emerged as the most powerful ruler of his time. He expanded his kingdom towards the River Severn at the expense of Wessex before joining with a British king, Cadwallon from Wales, to defeat and kill King Edwin, the Christian ruler of Northumbria, at Hatfield Chase in 632. Edwin's nephew Oswald returned from exile in the Christian monastery of Iona and he reunited Northumbria under his rule. In 642 Penda defeated Oswald , who was killed at the battle of Maserfield. Northumbria again split into the two sub-kingdoms of Deira and Bernicia and Penda became the most powerful ruler in Angleland. In 653 he defeated and killed another fellow-ruler, King Anna of the East Angles. In 655 he invaded Bernicia, now ruled by Oswald's brother Oswiu. It was a step to far: The mighty King Penda was killed in the battle of Winwaed and Northumbria rose again to become chief among the English kingdoms.

Oswiu's great achievement, in the eyes of the monks who wrote the history of the times, was the Synod of Whitby which unified the Celtic and Roman churches in 664. However, by 680 Mercia had once more subdued its rival Northumbria and became the dominant kingdom under King Offa during the later part of the eighth century.

Offa exercised control over much of eastern and south eastern England in addition to the Mercian Midlands. Mercia, like almost all of Anglo-Saxon England had become Christian by that time. Offa built the earthworks which still bears his name and acted as a barrier between Mercia and the Celtic Britons of Wales. In 785 Offa also ordained that 240 silver pennies of high quality should be minted from a block of silver weighing one Tower pound (a tower pond is an archaic measure long since disused, but 240 pennies continued to be worth one pound sterling until decimal coinage was introduced to Britain in 1971). Mercia’s trade and security was perhaps assisted by the Rivers Severn, Dee, Trent and Thames and the Fenland streams converging on the Wash, which roughly marked the Mercian boundaries and allowed river traffic to penetrate deep within its territory. Mercia's predominance was finally overcome in 825 when it was defeated at the Battle of Ellendun by Ecgberht, king of the emerging power of Wessex.

Kings, throughout the Anglo-Saxon era, were often absolute rulers. However, their power was often challenged by family contenders or powerful rivals and the king would usually consult with a council of advisors on matters of state. The king’s council evolved from the old Germanic tribal assemblies and became known as the Witan or Witenagemot. The most powerful soldiers, together with older men of experience and knowledge served the king in this way. As the kingdoms became Christian, bishops and abbots usually became important servants of the state and were called to attend the Witan.

Forms of social organisation varied slightly from kingdom to kingdom, but throughout England the ealdorman emerged as the next in secular importance to the king. The ealdorman was a powerful noble who exercised administrative authority on behalf of the king over a large area, such as a shire. The office of ealdorman was introduced when kings found it difficult to keep personal control of their expanding realms.

Ealdormen were sometimes of royal birth but were often chosen from the ranks of the thegn or thane. The thegn was a nobleman who could inherit or earn his title by soldierly prowess, or as a wise counsellor to the king. The thegn provided the king with military support and served in the Fyrd (a sort of militia) when required, either as part of a defensive force or on short offensive campaigns. He provided the arms, equipment and supplies for the war-band he brought with him to serve the king. He was rewarded with extensive landed property from which he financed and manned his military commitments.

Below the noble rank, most inhabitants were freemen known as ceorls or churls. They farmed the land, fished the rivers and seas and had the right to bear arms. Sometimes they followed their thegn to serve in the Fyrd in times of strife. Military campaigns were usually short; the men needed to attend to their farming duties at the time of seed sowing and harvest and warfare was usually confined to the summer months of May to early August. Sometimes, after a poor harvest, war parties would go on the rampage in October and November seeking to steal the harvest product from rival territories.

At the bottom of the social heap were the unfree labourers and slaves. The labourer was known as a cottar; although he was part of the community and often held a small parcel of land, he needed to work for others in order to earn a precarious living and had few or no communal rights. Slaves were merely chattels. If a slave were killed, injured or raped, the aggrieved owner was entitled to claim compensation from the offender for the damage to his property, but the slave was entitled to no recompense. Originally, many British captives were enslaved; later enemy captives and convicted criminals were added to their number. In hard times, some of the cottar class felt compelled to sell themselves and their families into slavery to avoid starvation.

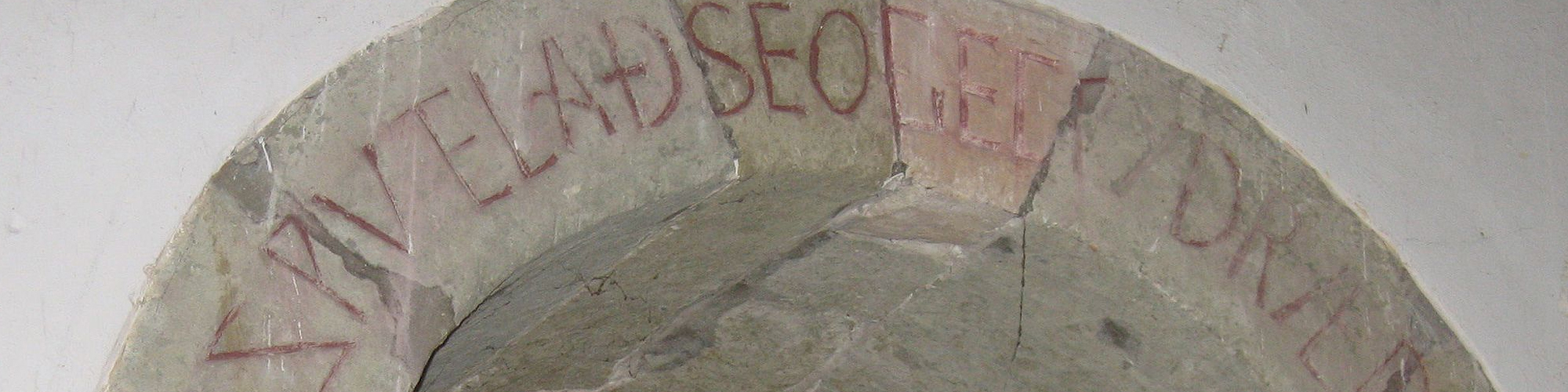

In early times the English wrote in runes inscribed on wood, stone or metal. They had no alphabet. However, they enjoyed a spoken culture of poems and sagas, such as the great saga of Beowulf, which were recited and sung by poets for the entertainment of all in the halls of the kings and thegns.

By the late sixth century, the old pagan culture of the original Germanic tribes in southern England was being challenged by the Christian message coming from Europe. Aethelbert King of Kent married Bertha, a Frank princess and a Christian. In 597 they became hosts to St Augustine at Canterbury when he was sent by the Pope to begin his ministry to convert the heathen English to Christianity. Quite quickly, itinerant priests were converting folk across Kent and Essex.

A slightly different form of the Christian message, left over from the time when Christianity was the state religion in Roman Britannia, was already established in Wales and the Western Isles, where Irish monks had established a monastery on the Isle of Iona. Soon the Celtic church was also evangelising from the monastery which St Aidan established on the Isle of Lindisfarne in the English kingdom of Northumbria. Eventually, as already mentioned, the two churches in England recognised the supremacy of the Pope at the Synod of Whitby and united behind the Roman message. By 680 St Wilfrid, a powerful bishop of the Rome Church, began to convert the people of Sussex, the last pagan kingdom in England.

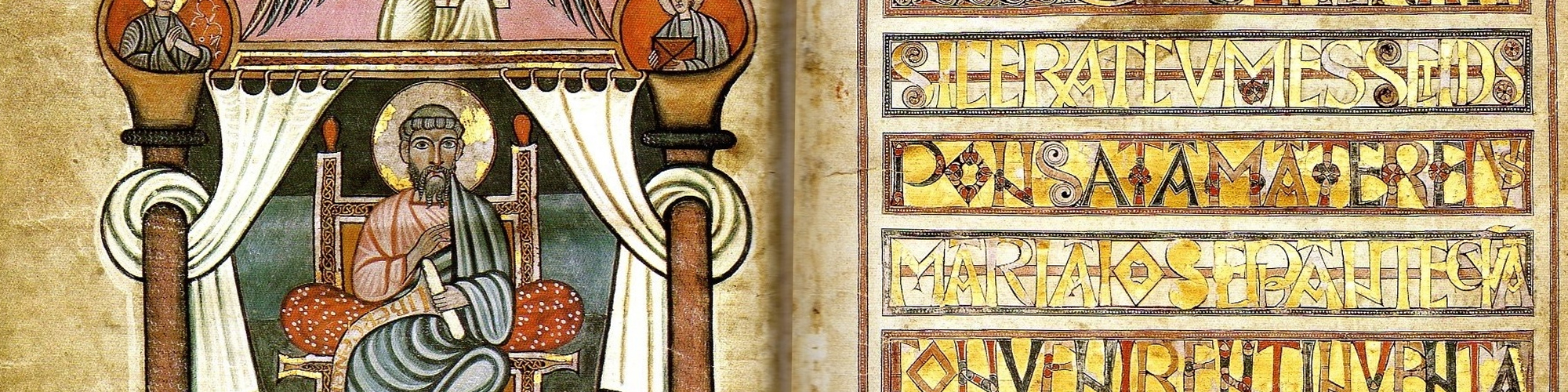

The spread of Christianity caused the English to abandon their old method of writing in runes and they adapted the Latin alphabet to their language. The churches spread literacy through the land again. Although the monks wrote mainly in Latin, the Old English language was used for keeping legal records of such things as wills, exchange of properties and some royal statutes. Aethelbert’s law code dating back to around the year 600 is the earliest surviving document written in the Old English language. During the next century Anglo-Saxon England, especially Northumbria, gained a reputation for sanctity and learning. The Venerable Bede of Jarrow was widely admired for his scholarship and Alcuin of York was recruited by Charlemagne, who had become the ruler of most of Western Europe, as teacher at his palace school in Aachen.

Beautiful illuminated books produced in monasteries demonstrate the high level of decorative art which was attained at that period in Anglo-Saxon England. This was matched by the fine workmanship exhibited in the ornate metal-work and jewellery found in the treasures of the heathen ship burial at Sutton Hoo and the recently-discovered Staffordshire Hoard which was probably hidden away no later than 675. With more artefacts coming to light every year as a result of archaeological excavations and the activities of metal detectorists, there is ample evidence that by the end of the seventh century England was a wealthy country which supported a thriving population of gifted artists and craftsmen.

However, before Wessex could assert its authority over Mercia and the rest of England it had to face up to a dangerous new enemy. As in the previous Romano-British era, the wealthy and cultured country of Britain attracted the attention of marauders from across the North Sea. The Vikings first appeared in the late eighth century and began to plunder the rich abbeys and halls of a country unused to dealing with the murderous onslaughts of a merciless enemy, who withdrew in swift ships before an adequate armed band could be assembled and deployed in response.

[/swpm_protected]

Timeline

430 Pagan immigrants, Saxons supposedly led by Hengist and Horsa, begin to settle in Kent as ‘protectors’ of the (Romano-Celtic) British.

447-50 Angles, Saxons, Jutes and Frieslanders join the earlier settlers in the south and begin the wholesale colonisation of eastern and southern Britannia. They eventually form several small kingdoms but eventually become collectively known as the Anglelanders or English.

[swpm_protected]

431 Palladius is ordained by the Pope as the first bishop to lead a Christian mission to the Christian ‘Scotii’ of Leinster in Ireland (Hibernia) but he was soon banished.

461 The traditional date for the death of St Patrick, patron saint and missionary bishop who brought Christianity based on monastic institutions to Ireland from his Romano-British homeland in Britannia. Alternative date 492/3 is now preferred.

470-500 British natives, many of whom are Christians, are driven west into Wales, Cornwall and the North West, where they are confined by the pagan English.

516 Possible date of the Battle of Mount Badon where the mythical British King Arthur supposedly defeated the English under king Aelle of Sussex.

540 Attributed date for the Ruin and Conquest of Britain written by a British monk named Gildas, the source for dubious histories written by later chroniclers.

563 St Columba (521-597) from Ireland establishes a monastery at Iona, Caledonia, which becomes the main centre of the Celtic Christian church in Britain.

569 St David (c500-589), later to become the Patron Saint of Wales, presides over the Synod of Caerleon and strongly opposes the heresy of Pelagianism.

Circa 584 Creoda, first known King of Mercia, founds a fortress at Tamworth.

593 The Anglian kingdoms of Deira and Bernicia are united by King Aethelfrith (died c616) and later become the kingdom of Northumbria.

597 Pope Gregory I (c540-604) sends St Augustine (died 604), first Archbishop of Canterbury, to Kent where he begins the conversion to Christianity of the southern English.

Circa 603 Aethelfrith, Anglian King of Bernicia and Deira, wins the battle of Degsastan against Aedan King of Dal Riata the Gaelic region of west Caledonia and north Hibernia.

616 The first English laws are issued by King Aethelbert of Kent (c550-616), perhaps the most politically developed of the English kingdoms at this time.

~ Edwin (c586-633) succeeds Aethelfrith as King of Northumbria (the unified kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira). Eventually he becomes acknowledged as Bretwalda (high king) by the southern kingdoms.

Circa 624 Death of Raedwald, King of the East Angles, probably buried in the ship burial uncovered in 1939 at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk.

627 King Edwin of Northumbria is baptized in the Christian faith.

628 The heathen King Penda (died 655) of Mercia takes Cirencester from Wessex and expands his kingdom to the river Severn.

632 Battle of Hatfield Chase. King Penda of Mercia and Cadwallon of Gwynedd defeat and kill King Edwin. They divide his kingdom of Northumbria.

633 Oswald (c604-642), nephew of Edwin, returns from exile in Iona, defeats and kills Cadwallon near Hexham, re-unites the kingdom of Northumbria and becomes Bretwalda.

634 St Aidan (died 651) from Iona establishes a Celtic Christian monastery on the Isle of Lindisfarne in the Anglian Kingdom of Northumbria.

642 King Penda of Mercia defeats and kills Oswald, King of Northumbria, at the battle of Maserfield. Oswald is celebrated as a martyr of the Celtic church. For a time Northumbria splits back once more into the separate kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira.

645 Penda of Mercia exiles Cenwalh King of Wessex to East Anglia for discarding his wife, who is Penda’s daughter.

655 King Penda is slain at battle of the Winwaed by Oswiu brother of Oswald and King of Deira who reunites Northumbria and becomes recognised as Bretwalda by the other English kingdoms.

~ Peada, son of Penda, becomes a Christian in order to marry Oswiu’s daughter and is allowed to rule in southern Mercia.

656 Peada is murdered and Oswiu of Northumbria assumes kingship of the entire Mercian kingdom.

658 Oswiu is overthrown in Mercia and Wulfhere (died 675), younger son of Penda, becomes king.

661 Wulfhere King of Mercia puts pressure on Wessex and takes the Isle of Wight, where he makes arrangements for the provision of Christian baptism.

664 The Synod of Whitby settles disputes between the Roman and Celtic churches. Rome’s supremacy, promoted by Bishop St Wilfrid (634-709/10), is recognised. Bishop of Lindisfarne Colman (c605-675) and his Celtic monks return to Iona and thence to Ireland.

~ The King of the East Saxons dies and his two sons succeed under the overlordship of Wulfhere of Mercia who now dominates England from the Thames valley to the Humber.

672 Queen Etheldreda (c630-679), wife of Ecgfrith (645-685) king of Northumbria becomes a nun and founding Abbess of Ely.

674 Wulfhere of Mercia is defeated by Ecgfrith of Northumbria and loses Lindsay (now part of the county of Lincolnshire). He dies the next year, succeeded by his brother Aethelred (died c705).

676 Aethelred of Mercia re-asserts Mercian dominance with the destruction of Rochester in Kent.

679 Aethelred defeats Ecgfrith of Northumbria at the battle of Trent and takes back the sub kingdom of Lindsay.

Circa 680 St Wilfrid begins the conversion of Sussex, the last pagan kingdom in England.

~ Latest estimated date for composition of Caedmon’s Hymn, the first surviving poem in English written by Caedmon, a Northumbrian monk.

685 The Picts defeat and kill King Ecgfrith of Northumbria at the battle of Dun Nechtain, freeing much of Caledonia north of the Forth from its Anglian overlords.

~ Caedwalla (659-689) becomes King of Wessex.

Circa 686 Caedwalla of Wessex breaks the Mercian control of Sussex and the Isle of Wight where he exterminates the ruling dynasty and forces Christianity on the population. He also invades and lays waste to parts of Kent after his brother, whom he has installed as king, is burned.

687 Cuthbert (born c634), monk, hermit and bishop, dies at Lindisfarne and becomes revered as a saint.

688 Caedwalla of Wessex, suffering from wounds, abdicates and goes to Rome where he is baptised. He is succeeded by King Ina (born 670).

692 Synod of Tara. The Celtic Church in Ireland submits to the authority of Rome.

694 King Ina of Wessex issues a code of laws some of which suggest a manorial form of open-field farming was developing. Others apply separately to British inhabitants of Wessex or subordinate territory.

704 Aethelred of Mercia abdicates and becomes a monk.

710 Ina of Wessex conquers the Britons of Dumnonia and takes Devon into Wessex.

716 Aethelbald (died 757) returns from exile and becomes King of Mercia following the relatively brief reigns of the two previous kings.

717 Nechtan King of the Picts expels Celtic monks and adopts the rule of the Roman Church.

722 Ina of Wessex campaigns against Sussex which he accuses of harbouring a rival.

726 Ina of Wessex abdicates and makes pilgrimage to Rome where he dies.

~ Aethelbald King of Mercia establishes hegemony over the southern kingdoms of England including Wessex and Sussex. London also falls under Mercian control about this time.

731 The Venerable Bede (672/3-735), a monk at Jarrow, Northumbria, completes The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, a valuable source of Anglo-Saxon history.

735 York becomes England’s second archbishopric.

756 Edbert King of Northumbria, allied with the Picts, campaigns in the British kingdom of Strathclyde and takes Dumbarton.

757 King Aethelbald of Mercia is murdered by a bodyguard and is succeeded by Offa (died 796).

771 King Offa of Mercia has become overlord of Kent and Sussex.

778 King Offa ravages the British princedom of Dyfedd.

782 Alcuin of York (c735-804), poet and scholar is appointed master of Charlemagne’s palace school at Aachen.

784 Offa, King of Mercia builds his dyke to define the English-Welsh/British border.

786 Cynewulf King of Wessex is murdered, Beorhtric (died 802) succeeds him and Egbert, a possible rival, is banished.

787 King Offa issues the silver penny, the only coin used in England for nearly 500 years. Coins of about the same value (1/240 lb sterling) remain in use until 1707.

793 The Viking raids begin. Vikings (Danes or Norsemen/Norwegians) from Scandinavia attack Lindisfarne monastery.

794 Aethelberht II King of the East Angles is beheaded, possibly for rebelling against his overlord Offa of Mercia.

795 Vikings burn the monasteries of Iona and at Rathin Island, the beginning of a sustained period of raids on Scotland and Ireland.

796 Death of King Offa. Beginning of Mercia’s decline as the most powerful English kingdom.

[/swpm_protected]